Was the Christmas Tree in Union Square, San Francisco, Really Emperor Norton’s Idea?

This is part of our occasional series of Open Questions articles. These articles take "deep dives" into some of the most oft-repeated — but under-analyzed — historical claims about Joshua Norton / Emperor Norton. They offer source material for future exploration of questions that generally are presented as settled — but aren't.

:: :: ::

THE SHORT ANSWER is: It seems not.

But, the long answer is more interesting.

A certain legend about Emperor Norton is related in a little booklet, San Francisco’s Emperor Norton, written and self-published in 1939 by David Warren Ryder.

Another story which has come down to us without benefit of the credentials of authenticity, but which has persisted nevertheless, is the one concerning a public Christmas tree in Union Square at the Emperor’s instigation.

As usual, the Emperor introduced the idea through one of his famous Imperial proclamations; which, as was his custom in such matters, he circulated among the city’s larger business firms.

It so happened that one of these chanced to fall into the hands of a prominent San Francisco merchant — a man who long had known Emperor Norton and liked him and who on several occasions had cheerfully paid on of his Imperial “levies.”

This man had read the proclamation and was at once struck with the novelty and nobility of the Emperor’s proposal. “Why not,” he asked himself, “do what the Emperor orders, and do it in the Emperor’s name?” Whereupon, he proceeded to confer with his business associates throughout the city, and they, too, immediately fell in with the idea. So a committee was formed, and a score of busy San Francisco merchants, lawyers, doctors, etc., went to work with a will; with the result that the Emperor’s noble idea became a beautiful reality. The tallest fir tree ever seen in San Francisco was put up in the center of Union Square, and with its long ropes of tinsel, and its thousands of candles, it made an impressive and a lovely sight.

It was a notable occasion, and one long-remembered. The city’s finest band played Christmas music, and a chorus of a hundred voices sang Christmas carols; while a score of busy Kris Kringles gave out thousands of bags of candy and fruit and nuts to the assembled children. And hard by the big Christmas tree, on a red and green throne, sat Emperor Norton, wearing a new uniform which the committee had provided; beaming and smiling and waving to the children as they marched by and called out their greetings to him. He was so happy he could scarcely contain himself, and so excited that when it came time to go, he had to be helped down and into the carriage the Committee had hired to take him home.

This public festival in celebration of the birth of the Christ Child may well have been to the kindly old Emperor the crowning event of his kindly reign. The exact date of it has been lost in the dimness of old men’s memories, but it has been placed by some in the year 1879.

If so, it was probably Emperor Norton’s last public appearance.

:: :: ::

IT’S A LOVELY story — but...

Given local newspapers’ longstanding preoccupation with the comings, goings and Proclamations of Emperor Norton, it’s very difficult — almost impossible — to imagine that such a fantastic public spectacle as Ryder describes, with the Emperor at the center of it all, could have escaped being written up in the city’s biggest broadsheets.

(As it happens, Ryder’s booklet is a font of apocryphal tales — tales that, having been taken literally by subsequent generations of overly credulous subjects of the Emperor — It’s in print! It must be true! — have become fixtures of the Norton mythology. This includes Ryder’s undocumented claims that Emperor Norton penned a proclamation against the use of the word “Frisco” — and that the Emperor once quelled an anti-Chinese mob by standing amongst them and reciting the Our Father over and over.)

A careful review of the archives of the San Francisco Chronicle and the San Francisco Examiner — two papers established early in the Emperor’s reign and published continuously since then — finds no mention of any large Christmas tree in Union Square, with or without attribution to Emperor Norton, during the Emperor’s lifetime.

Ditto for such a display in the decades immediately following Emperor Norton’s death in January 1880.

An additional claim that frequently attaches to the Norton Christmas tree story is that the first Christmas tree in San Francisco’s Union Square was the first outdoor — thus, truly public — civic Christmas tree in the United States.

In fact, that distinction basically is shared by Boston, New York and Hartford, Conn. — which switched the lights on their respective civic Christmas trees within a half-hour period from about 5 to 5:30 p.m. on Christmas Eve 1912. (The wonderful 2011 essay here expands on the reasons why the idea of a public civic Christmas tree was advanced in the first place.)

Here’s the 1912 Christmas tree in New York’s Madison Square Park:

The Christmas tree in Madison Square Park, New York City, on Christmas Eve 1912. This was one of the first outdoor civic Christmas trees in the United States. The other two — in Boston and in Hartford, Conn. — were lit that same evening. Photograph: Collection of the Library of Congress. Source: 6sqft

To be fair, San Francisco was only a day late. On Christmas Day 1912, the city lit its first outdoor municipal Christmas tree — a “monster” tree surrounded by six smaller trees — at a Christmas tree festival in Golden Gate Park Stadium (now known as the Polo Field). Newspaper estimates put the crowd at more than 10,000 children and adults. The Stadium celebration was repeated in 1913.

Christmas tree celebration in Golden Gate Park Stadium, Christmas Day 1912 — the first outdoor municipal tree in San Francisco. Possibly a detail from a larger photograph. Marilyn Blaisdell Collection. Source: OpenSFHistory/wnp37.04263.jpg

In 1914, the city’s Christmas tree celebration moved to the not-quite-finished grounds of the soon-to-open Panama-Pacific International Exposition (PPIE) — the tree was in the Court of the Universe, in the shadow of the Tower of Jewels — and was back at this location for the final post-exposition event, on Christmas Day 1915.

The municipal Christmas tree in the Court of the Universe at the Panama-Pacific International Exposition, San Francisco, Christmas Day 1914. The PPIE grounds are still under construction. Click for a wonderful much-larger view. Photo postcard in the private collection of Glenn Koch. Source: Glenn Koch.

After a return to Golden Gate Park — to the Children’s Playground — in 1916 and an indoor display at the Civic Auditorium in 1917, San Francisco’s municipal Christmas tree moved to Civic Center, where the tree had its outdoor debut in 1918.

In the days leading up to the 1918 celebration, the San Francisco Chronicle reported that workers were setting up an elaborate and powerful lighting system, and that “a towering and wonderfully decorated Christmas tree” would be “sparkling with 10,000 brilliants from the Tower of Jewels as a background.”

Apparently, these “brilliants” were among the 102,000 colored, cut-glass, mirror-backed, brass-hangered, made-in-Bohemia Novagems that had hung on the Tower of Jewels during the PPIE and now were being repurposed as spectacular baubles for the tree.

The tree was back at Civic Center in 1919 and intermittently in the following decades.

Gathering at the foot of the municipal Christmas tree in Civic Center, San Francisco, 1919. Sixth from right is San Francisco Mayor James Rolph. Photograph in the Jesse Brown Cook Scrapbooks Documenting San Francisco History, c.1895–1936, Bancroft Library, UC Berkeley. Source: Calisphere.

:: :: ::

In 1927, the San Francisco Examiner put up the first of its enormous lighted Christmas trees at the top of Twin Peaks. The paper repeated this promotion in 1928 and 1929.

BUT, based on newspaper records, it appears that the first Christmas tree in Union Square wasn’t raised until 1929 — fifty years after Emperor Norton’s death.

“Raised” is a bit of a euphemism, as the “tree” really was a monumental tree-shaped fabrication that placed large, natural fir trimmings on a temporary structure built around — and masking — the 105-foot-tall Dewey Monument, in the center of the square.

But, the 105-foot “tree” was a very big deal — the anchor of a first-of-its-kind “Month-Long Yule Fete” announced in the San Francisco Chronicle on 7 November and promoted in the paper virtually every day for the next six weeks, with a tree lighting and entertainment in Union Square every day until Christmas Eve.

PDF of full original article here. Source: San Francisco Public Library

The basic contours of the festival’s inaugural event on 30 November were similar to what David Warren Ryder described in his 1939 account. The event and the larger festival was promoted and funded by a business group — the Down Town Association, founded in 1907 in the wake of the earthquake and fires of 1906. There was a parade with thousands of children. There were bands playing Christmas music. There was a gigantic tree in Union Square. And there was a throne adjacent to the tree.

But, the figure at the center of it all was not Emperor Norton — it was Santa Claus.

Nor, alas, was the Emperor invoked as an inspiration for the tree.

Plans were for a companion 100-foot-tall fir Christmas tree in front of the Ferry Building, with the 30 November children’s parade making its way along Market Street from the tree at the Ferry Building to the one in Union Square.

The Saturday-morning parade — which served as the opening ceremony for the month-long celebration — went off with appropriate fanfare. Presiding over the festivities was Santa Claus, who, once the parade had reached its destination in Union Square, was presented with a large Key to the City made of flowers.

PDF of full original article here. Source: San Francisco Public Library

But, the trees weren’t quite ready.

The Union Square tree, festooned with 3,000 electric lights and ringed around the base with larger-than-life cutouts of children’s storybook characters, was dedicated and lit before thousands of onlookers on Saturday 7 December. The tree at the Ferry Building was rolled out the following weekend, on Friday the 13th. Mayor James “Sunny Jim” Rolph and Santa Claus, together with a host of business, civic and political leaders, were on hand for all three events — each of which the Chronicle gave bold headlines the day before, the day of and the day after.

PDF of full original article here. Source: San Francisco Public Library

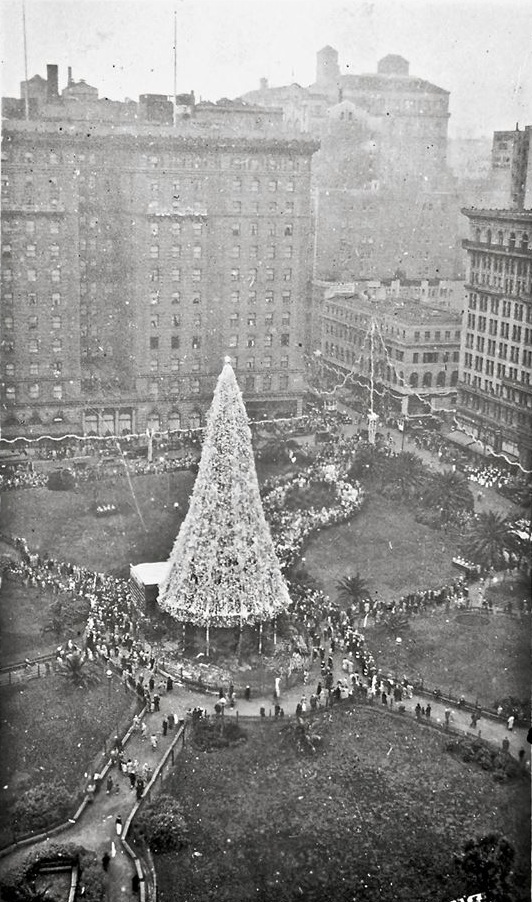

Here’s the 1929 tree in daylight.*

Christmas tree in Union Square, San Francisco, December 1929.* Collection of the Oakland Public Library History Room. Source: Bennett Hall

And at night.* Santa’s throne was under the striped canopy.

Christmas tree in Union Square, San Francisco, December 1929.* Marilyn Blaisdell Collection. Source: OpenSFHistory/wnp37.01765.jpg

This highly choreographed “fête,” including the Union Square Christmas “tree” — lauded as “glorious,” “majestic,” “towering” and every other apt superlative that San Francisco Chronicle reporters and editors could rustle out of their word bags — was back for the 1930 holiday season. In keeping with the theme of “White Christmas” for the 1930 fête, the tree that year was flocked with white, with a dozen large red and white candle-shaped lights around the base.

Here’s the 1930 tree.* A “log cabin” was built for Santa that year. Santa’s cabin is just visible on the west side of the tree, facing the Hotel St. Francis.

Christmas tree in Union Square, San Francisco, December 1930.* Photograph taken by Francis Joseph Sperisen (1901–1986) from his lapidary shop in the Whittell Building, at 166 Geary Street. (Photograph of the Dewey Monument and the Whittell Building, courtesy of Sperisen’s niece, Ramona Walker.)

In January 1931, Angelo Rossi was appointed the new Mayor of San Francisco — James Rolph having been elected Governor of California the preceding November. On 22 May 1931, readers of the Chronicle learned that, on the third go around, Rossi and downtown business leaders wanted a different kind of Christmas tree in Union Square:

The cool Pacific breeze that shooed the hot spell brought a new thought to City Hall yesterday. Mayor Rossi announced that this year San Francisco is going to have a real, honest-to-goodness Christmas tree.

The Northwest is going to be scoured for its most gargantuan fir tree. The Down Town Association, which sponsors the municipal Yuletide decorations, and the Mayor are off artificial Christmas trees for life. “We don’t want any more contour-less things like we had in Union Square last Christmas. We want a real tree,” they agreed yesterday in the Mayor’s office.

“We spent $42,000 last year. Well, we’re going to spend more than that next Christmas time.”

Apparently, the promised tree never materialized. Indeed, a Letter to the Editor that the Chronicle published on 18 December 1931 suggests that there was no Christmas tree at all in Union Square that year. Reader F.N. Schenke was not at all happy about this [emphasis added]:

Sir: The cause of unemployment certainly has not been helped by the lack of community Christmas decorations and community Christmas trees. Where is the tree in Union Square and the one on Twin Peaks? Where are the Christmas garlands along our streets, which helped to cheer multitudes of sad, weary hearts?

We, in our homes, are putting aside all thought and talk of depression, putting our best foot forward during this holiday season, decorating our homes, and it is certainly not too much to ask that our city does the same. I would also suggest that our big buildings — formerly so beautifully decorated, cheer us with their fairylike structures, as in the past.

:: :: ::

IN FACT, it appears that it would be another 50 Christmas seasons before there was a tree in Union Square on anything like the scale of the trees of 1929 and 1930 — or, indeed, anything that rightly could be considered “the” Christmas tree in Union Square.

The Down Town Association continued to sponsor Christmas decorations in Union Square, often in cooperation with the San Francisco Department of Recreation and Parks. But, the focus shifted away from a single, monumental Christmas tree towards Christmas “lights.” (The mistaken claim that there has been a big Christmas tree in Union Square “every year” since the Emperor’s day turns out to be another embellishment on David Warren Ryder’s manufactured legend of 1939.)

For example:

In 1942, following the completion of a new garage beneath Union Square, a redesigned Union Square Park was unveiled. The new park featured the addition of 16 yew trees, and there was a proposal in 1943 to light these trees for Christmas. Holiday lighting of the yews didn’t begin until 1950 — but, this started a tradition that seems to have continued until quite recently, when the yews were removed as part of the most recent renovation of the park, a few years ago.

In December 1946, the Chronicle noted the temporary addition of four 30-foot-tall cypress trees — also ceremonially lit — to the Union Square holiday mix. This appears to have continued for about a decade, perhaps a little less.

In 1955, the Salvation Army set up its first “Tree of Lights” in Union Square — a 40-foot-tall Christmas tree whose lights were illuminated to reflect the group’s advances in meeting its holiday fund-raising goal. This tree, which was separate from the civic decorations, was presented during the holidays until the late 1960s.

Throughout this period, from the 1930s through the 1960s, the Christmas tree that most people wanted to see when they were in Union Square was the legendary indoor tree in the rotunda of the City of Paris department store, on the southeast corner of Stockton and Geary Streets.

The tree wasn’t 100 feet tall, like the civic trees at the center of Union Square in 1929 and 1930. But, it was unfailingly fabulous across 64 years of holidays, from 1909 until 1973. (The store closed the following year.)

Christmas tree at City of Paris department store, 23 November 1959. Photograph © San Francisco Chronicle (Gordon Peters). Source: San Francisco Chronicle

:: :: ::

IT WASN’T until 1983 — a decade after the final City of Paris tree — that San Francisco saw another Dewey Monument-scaled civic Christmas tree in Union Square Park, i.e., a tree to compare in magnetism and sheer monumentality to the trees of 1929 and 1930.

The tree, sponsored by the recently formed Union Square Association, was another “tree” in quotation marks — this time, without even the pretense of being a “real” tree. Like the sylvan towers constructed two generations earlier, the “84-foot imitation tree” was “constructed around the Dewey Monument.” But — reflecting its time — this tree “sparkled with a computer-run show of strobes, miniature and diamond lights, set with mylar garlands and glittering pinwheels,” according to the Chronicle. Angelo Rossi would have hated it.

Christmas tree in Union Square, 25 November 1983. Photograph © San Francisco Chronicle (Frederick Larson). Source: San Francisco Public Library

The Union Square Association continued to sponsor Christmas trees of various sizes — including real ones — in Union Square through the 1988 holiday season. But, money was becoming an issue. And, in 1989, Macy’s took over the funding and presentation of the annual Christmas tree in Union Square.

Christmas tree in Union Square, San Francisco, 1996 or 1997. Photograph © Ray Morse

From 1989 to 2010, the Macy’s Christmas trees were very large, natural trees raised alongside the Dewey Monument.

Starting in 2011, Macy’s switched to the 86-foot-tall artificial Christmas tree — the highly stylized bright-green cone — that has stood watch over Union Square every holiday season since. (There’s an informative KQED story and video about the Macy’s tree here.)

:: :: ::

DESPITE the fabulous introduction of outdoor civic Christmas trees to Union Square in 1929 and 1930, there has been a sustained tradition of such trees only for the last 35 years — starting in 1983.

As for Emperor Norton…

The historical claim attributing to the Emperor the original idea for a Christmas tree in Union Square appears to be wishful thinking based on the romanticized legend concocted by David Warren Ryder in 1939.

Notable, though, is how often newspaper coverage of the Christmas fêtes of 1929 and 1930 refer to Santa Claus as a “monarch” and to children and adults alike as Santa’s “subjects.” On 1 December 1930, a San Francisco Chronicle headline declared: “Santa Claus to Rule for Three Weeks; Children from 7 to 70 Will Pay Court to King of Christmas.” There even was a newspaper Proclamation from Santa Claus in each of those years.

Emperor Norton was known for his tenderness and kindness towards children. And, writers in the generation or two after the Emperor’s death, recalling their childhood encounters with him in San Francisco, often remembered the Emperor as a Santa Claus figure.

Depending on one’s perspective, the line between Santa Claus and Emperor Norton can get a little blurry.

That’s worth remembering in this and every holiday season.

* Research for this article produced dates (month/year) for three photographs of Christmas trees in Union Square (asterisked above) that previously either were incorrectly or imprecisely dated or were undated.

:: :: ::

For an archive of all of the Trust’s blog posts and a complete listing of search tags, please click here.

Search our blog...