Is This Really Joshua Norton?

Century-Old Claims for Portrait Photograph Appear to Be Rooted in Wishful Thinking

BY THE TIME he died in 1927, Charles Beebe Turrill (1854–1927) was regarded — in California, at least — as having one of the world’s most significant private collections of books, manuscripts, photographs, and ephemera related to the early history of California.

From his residence at 57 Sanchez Street, San Francisco, Turrill presided over his collection as a kind of library and research institute. Photographs were a particular obsession — not surprising given that Turrill himself was, by trade, a commercial photographer. According to one 1925 account:

In his little den, piled high with stacks of old periodicals, papers, documents, and, as he frankly admits, junk, [Turrill] not only digs out historical photographs, but, so far as he can, the facts that go with them. Whoever takes a photograph away must first give evidence that what he’s going to say about it will be correct, that is, if it’s to be used to illustrate a published article.

In at least one case, as well see, Turrill’s stipulation about photographs may have been more aspirational than real.

:: :: ::

A 1927 ITEM about Charles Turrill’s will put a premium on his collection of “15,000 photographs of historical value”:

At around the same time, the Society of California Pioneers was looking for a way to rebuild its collection — which mostly had been lost in the earthquake and fires of 1906.

Typically, the Pioneers had built their collection through donations. But, in 1928 — in a measure of both the acquisitional opportunity and the urgency of the institutional moment — the Pioneers purchased the Turrill collection outright.

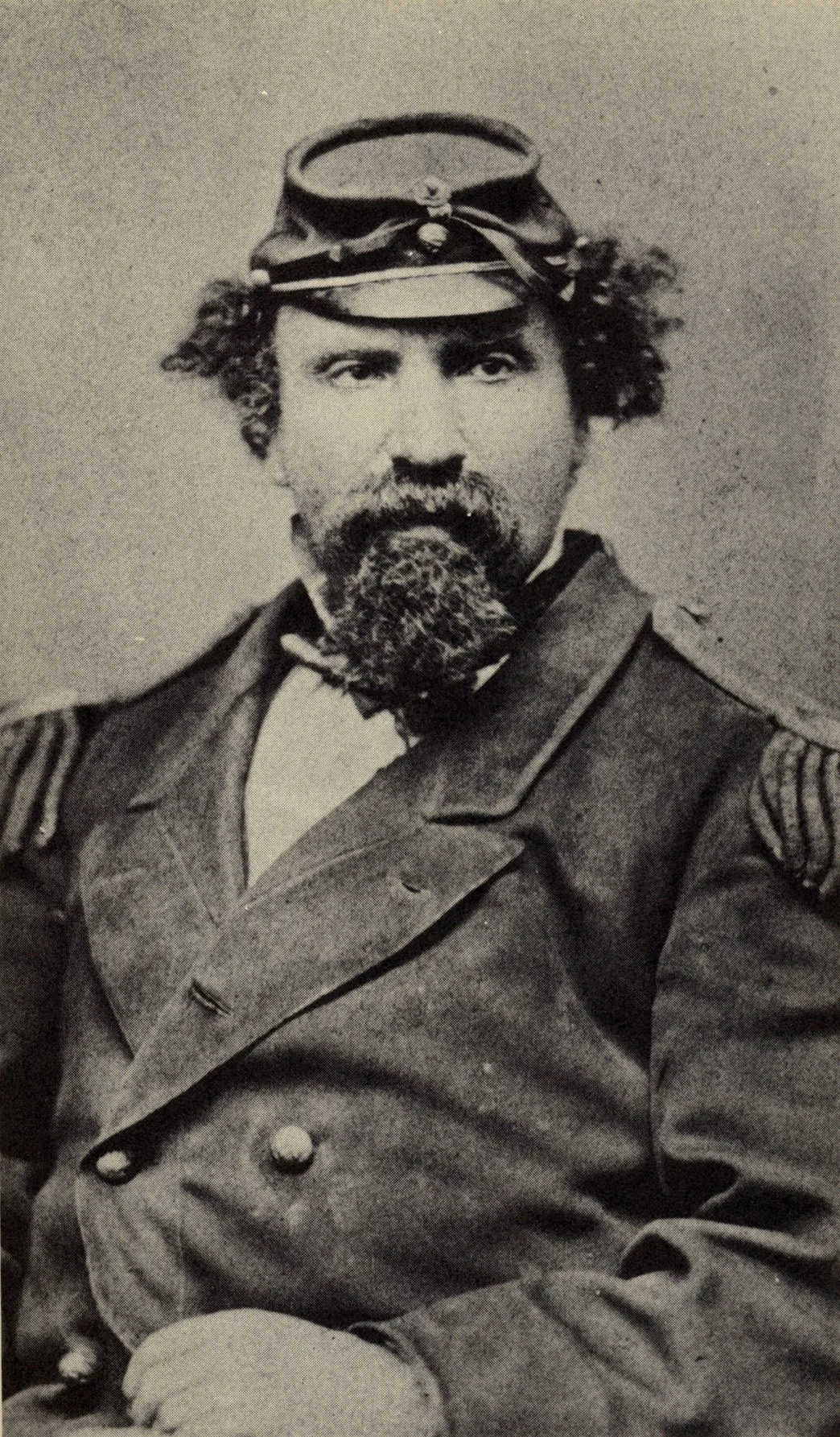

Included in the acquisition was the following photograph:

The Pioneers’ current catalog title for this item — reflecting the notations on the verso of the card above — is:

Emperor Norton / 1871 / in early life

The first hurdle to the credibility of this ID arrives early, with the first two elements of the title: “Emperor Norton / 1871.”

To wit: In 1871 — a dozen years into his reign — Emperor Norton did not look like the man in this photograph.

Reliably dated photographs have the Emperor looking like this in March 1869…

Emperor Norton, early March 1869. From a stereograph by Eadweard Muybridge (1830–1904), taken in front of the fourth Mechanics' Pavilion, at the northwest corner of Stockton and Geary Streets, San Francisco, during a “velocipedestrian training school” that was held at Pavilion starting in early February 1869. (See item from the Daily Alta California of 8 March 1869 here.) Source: Bancroft Library

…and like this sometime between spring 1871 and spring 1872:

Emperor Norton, c.1871–72. Detail from carte de visite by Tuttle & Johnson studio, 523 Kearny Street, "Heliographic Artists." To learn more, see our June 2017 article here. Source: California Historical Society Collection at Stanford

Given Turrill’s stature as an historian and collector of early California photographs, the Pioneers’ library staff of the late 1920s might have been reluctant to question or challenge Turill’s ID of any photo — especially if it was dated with a specific year.

Indeed, if the reported number of photographs in the Turill collection — 15,000 — is anything close to accurate, it stands to reason that — for practical reasons, too — the Pioneers simply transcribed Turrill’s IDs in creating their own catalog records.

And yet…

Something to notice about the verso of the photo card in the Pioneers collection is that the notations “Emperor Norton / 1871” and “in Early life” are written in different hands.

The following shows Turrill’s inscription “With the Compliments of the author.” that he wrote on the free front end paper of a copy of his only book, California Notes, a kind of hybrid travel guide / almanac published in 1876:

Image from dealer listing of copy of Charles Beebe Turrill’s California Notes (1876). Source: Biblio

Comparing this inscription with the notations on the verso of the Pioneers photo card, my bet is:

(a) “Emperor Norton / 1871” is Turrill’s ID; and

(b) “in Early life” reflects the effort of a Pioneers librarian(s) — whether during the initial acquisition / cataloguing period of, say, 1928–30 or at some later time — to finesse the obvious dating error that identified the subject of the photograph as Emperor Norton in 1871.

:: :: ::

THE “IN EARLY LIFE” cataloguing edit creates a conundrum, though.

In 1871, Emperor Norton — born in 1818 — was 53 years old. Not “early life.”

If the subject of the photograph is Emperor Norton, the subject can’t be shown both in “1871” and “in Early life.”

Whether it was a cataloguing oversight or an active cataloguing decision on the Pioneers’ part, the practical effect of allowing both “1871” and “in Early life” to stand — rather than allowing “in Early life” to correct and supplant “1871” — has been to force researchers who accept the basic “Emperor Norton” ID to choose which modifier they prefer. They can’t have both. They’ve had to pick one or the other.

Here’s a closer look at the photograph:

It appears that the first to publish this photo in a way that advanced a connection to Emperor Norton was Allen Stanley Lane (1889–1967), in his 1939 biography Emperor Norton: The Mad Monarch of America.

Lane captions the photo (on a plate slotted between pages 32 and 33) “Joshua Norton the Merchant.” The clear postulation is that this is Joshua in the early 1850s — a half-decade or more before he declared himself Emperor in 1859.

In his own way, Lane ignored “1871” and went with “in Early life.” Indeed, it’s possible that the “in Early life” notation was added as a direct and contemporaneous response to Lane’s research.

Nearly 50 years after Lane, William Drury (1918–1993) included the photograph in his own 1986 biography Norton I: Emperor of the United States. Drury digs in even further, captioning the photo (the first in a 10-page gallery between numbered pages 109 and 110): "Joshua Norton as a prosperous merchant and land owner about the time he joined the Vigilance Committee of 1851."

:: :: ::

BUT, TO DATE this photograph to the early 1850s is to climb out of one ditch only to jump into another — for a couple of reasons:

1

An historian of early photography and a specialist in the photographic panoramas of San Francisco by Carleton Watkins, Eadweard Muybridge, and W.H. Jackson, Nick Wright also runs the 43,000-member Facebook group San Francisco History to the 1920s.

Recently, having noticed The Emperor Norton Trust’s 2016 file name for the photograph we’re discussing here — “Joshua_Abraham_Norton_in_1851” — Wright posted the photo to the group, tagging me with the note: “I am not feeling 1851 for this photo.”

Wright pointed out that a portrait photo in the San Francisco of 1851 would have been a daguerrotype — but that this photograph bears the hallmarks of having been made using the later wet collodion process that did not start becoming popular until the mid 1850s before supplanting daguerrotype and subsequent transitional processes (like tintype) in the 1860s.

A material point that lies just below the surface of Wright’s comments — which planted the seed for the reassessment being offered here:

The subject photograph is a print — a copy.

But a daguerrotype is a one-time, NON-DUPLICABLE image that does not include the production of a photographic negative that can be used to make copies.

For this reason alone, the subject photo cannot have been produced c.1850–52, as Norton biographers Lane and Drury claim but must have been produced sometime after the advent and commercial use of collodion / photographic negative technology in the mid 1850s — and, more likely, was produced when the decade of the 1850s was in the rearview mirror.

2

The fashion signifiers, too — the cut of the jacket; the facial hair — are from the 1860s or later, not the early 1850s.

Chiming in to Nick Wright’s thread was John Boessenecker, a noted historian and author of books about crime in the Old West. Boessenecker commented flatly “That is a carte de visite from about 1870,” going on to say: “You can tell it is a CDV from the tone, color, and oval format. The clothing and hair style is late 1860s to early 1870s or so.”

The Fashion Institute of Technology (FIT) has a terrific decade-by-decade descriptive and illustrated trendline of fashion history. It’s worth looking at the men’s sections for the 1850s, 1860s, and 1870s, to see where, historically, the subject of the photograph we’re discussing may fall.

According to the FIT overview…

The overall silhouette of menswear remained narrow in the early 1850s, with closely-cut sleeves and trousers. At mid-decade, styles began to relax [with] jackets lengthened into longer, straighter cuts.…

For the majority of the 1860s, menswear was marked by an oversized appearance, with loosely-cut jackets [while] the 1870s [saw] the overall silhouette slimmed a bit from the boxy, oversized jackets of the 1860s.

Oversized, loosely-cut jackets like the one being worn by the gentleman in the photo?

The beard worn by this gentleman, too, reflects the “tonsorial experimentation” among men — my phrase — that didn’t really arrive until the Civil War. Below is an 1861 photograph featuring then-Colonel Ambrose Burnside (1824–1881), wearing his trademark “friendly muttonchops” beard, in which bushy sidewhiskers — later called “sideburns,” in tribute to Burnside — were joined by a moustache.

From the photo, it appears that Burnside’s shaving habit was iconoclastic at the time.

First Rhode Island Infantry Staff with Colonel Ambrose Burnside (center), 1861. Source: Library of Congress; Bull Runnings

Here’s a portrait of Burnside that at least one source dates to the same year:

After uncovering these early photographs of Burnside, I emailed Sarah Gold McBride, a lecturer in American Studies at UC Berkeley whose scholarly interests include, among other things, 19th-century hair and beard practices. Dr. Gold McBride’s first book, Whiskerology: The Culture of Hair in Nineteenth-Century America, was published last month by Harvard University Press.

I asked Gold McBride for her take on the Pioneers photograph — specifically, when beards like the one worn by the subject of the photo became common. Citing Burnside as an early tastemaker, Gold McBride writes:

Although I do not have any specific expertise in the beard fashions most popular among San Francisco merchants, I do agree with your hunch that this is not likely to be an 1850s photograph and was more likely taken in the 1860s or 1870s. The technological evidence, for one, feels strong: if this is indeed a print produced via wet plate collodion processing, then it seems quite unlikely to be an 1850s image. As for the visual evidence: the facial hair style in this photograph most closely mirrors, to my mind, Ambrose Burnside's facial hair (from which we get the phrase sideburns, an inversion of burnsides), which became popular after Burnside's role as a Union General during the Civil War. Although the Oxford English Dictionary's earliest entry for burnside(s) (as a facial hair type, not just in reference to the individual man Burnside) is from 1875, I can find examples as early as 1866 [see "On the Watch" item in column 1 here]. I'm not a fashion historian so I don't feel confident dating the clothing, but looking at other photographs of men from the 1860s and 1870s suggests that this man's outfit would certainly be at home in that era.

It seems that the penchant for growing friendly muttonchops in the particular style of our photographic subject — with sidewhiskers cascading down below the jawline — was indeed a later development, seen more commonly starting in the late 1860s and 1870s.

This style was popularized by King Kalakaua of Hawaii (1836–1891) and became known as a “hulihee,” for Kalakaua’s association with the Hawaiian royal vacation home known as Hulihe’e Palace.

Kalakaua began wearing his beard this way around the beginning of his reign in 1874.

Here he is about 1882:

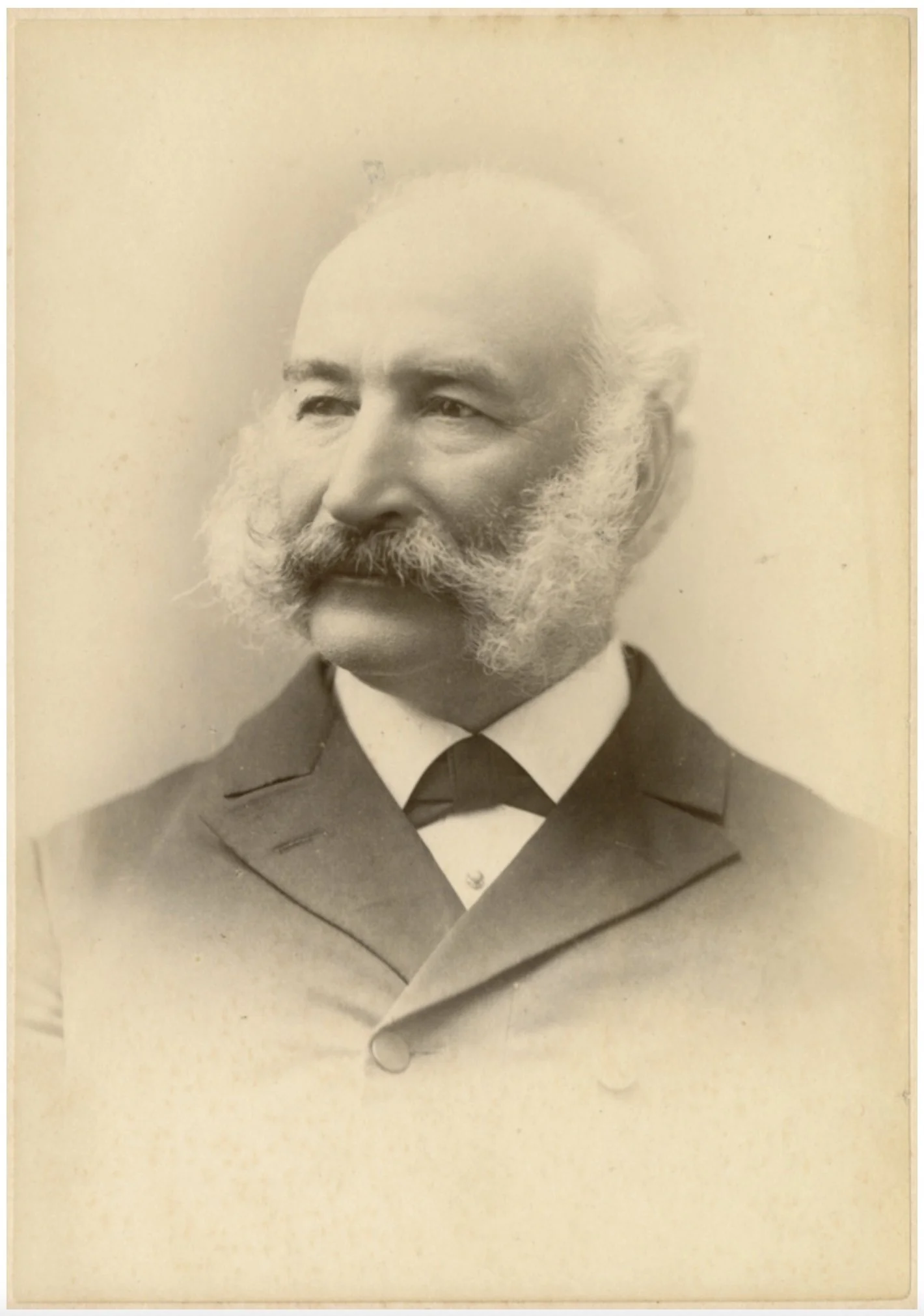

For comparison is this slightly earlier photograph of George Henry Williams (1823–1910) taken by Mathew Brady and Levin Handy — probably c.1871–75, while Williams was Ulysses S. Grant’s Attorney General.

George Henry Williams, c.1871–75, by Mathew Brady and Levin Handy. Source: Library of Congess (original) and Wikipedia Commons (restored detail)

There are countless other examples — Adolph Sutro (1830–1898), seen here c.1885, springs to mind.

But the high-water mark for the Friendly Muttonchops, Waterfall Edition beard worn by the gentleman in our discussion photo is the Gilded Age of the 1870s to 1890s — not the early 1850s.

:: :: ::

A FINAL observation…

The gentleman in our photograph is decidedly bald. He doesn’t have a “high forehead” or a “receding” hairline — there’s nothing up there.

Here’s Emperor Norton, c.1878:

It doesn’t seem likely that — having been a cueball in the early 1850s — the Emperor had sprouted unruly curls atop his pate 25 years later.

:: :: ::

GRANTED that we’re in the realm of probabilities here, not certainties — BUT…

Given the available visual and historical evidence and background, what seems most likely is that the photograph we’re assessing actually IS from 1871 (or thereabouts) — as the Pioneers, apparently using Charles Beebe Turrill’s information, have it — BUT that…

The subject is NOT Joshua Norton.

The Emperor Norton Trust will keep this photograph in our gallery for now — flagged and with a note that includes a link to this article, so as to help foster an active discussion around the photo.

But, we have removed the photograph from our biographical summary of Emperor Norton, as well as from the Trust’s other research articles and from image galleries associated with our interactive Emperor Norton Map of the World. We urge those who have included the photo in their own items about the Emperor to do the same.

:: :: ::

For an archive of all of the Trust’s blog posts and a complete listing of search tags, please click here.

Search our blog...